1. Introduction

1.1 Background of the Study

January 1st is globally recognized as the beginning of the New Year under the Gregorian calendar. Across societies, it is marked by celebrations, reflections, resolutions, and symbolic transitions. Despite its universal observance, January 1st has no inherent astronomical or natural significance that designates it as the start of a year. Instead, its importance emerges from historical decisions, institutional authority, and collective acceptance.

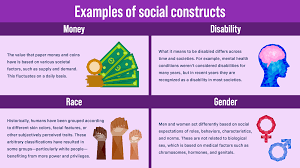

This study situates January 1st within the framework of social construction, arguing that time is not only measured but socially produced. Calendars function as cultural tools that structure social life, shape identity, and legitimize change. Understanding January 1st as a social construct allows for deeper insight into how societies organize time, reinforce shared meanings, and sustain collective renewal.

1.2 Problem Statement

Although January 1st is widely celebrated as New Year’s Day, it is often perceived as a natural and inevitable temporal boundary rather than a socially constructed phenomenon. This perception obscures the historical, cultural, and political processes that led to its global recognition. The lack of critical examination of January 1st as a social construct limits scholarly understanding of how time shapes identity, social cohesion, and collective behavior.

1.3 Objectives of the Study

General Objective:

To analyze January 1st as a socially constructed temporal marker and examine its influence on time perception, collective identity, and processes of renewal.

Specific Objectives:

- To examine the historical and social foundations through which January 1st became established as New Year’s Day, in comparison with alternative New Year celebrations across cultures.

- To analyze how January 1st functions symbolically and ritually in constructing collective identity and social cohesion.

- To assess the role of January 1st as a temporal landmark in facilitating individual and collective renewal.

1.4 Research Questions

· How did January 1st become established as New Year’s Day, and how does it compare with alternative New Year celebrations across cultures?

· In what ways does January 1st function symbolically and ritually to construct collective identity and social cohesion?

· How does January 1st act as a temporal landmark in facilitating individual and collective renewal?

1.5 Significance of the Study

This study contributes to sociology, anthropology, and cultural studies by highlighting time as a socially constructed phenomenon. It provides insight for scholars, educators, and policymakers on how symbolic dates influence social behavior, governance, and identity formation. The study also promotes cultural awareness by recognizing the plurality of temporal systems across societies.

2. Literature Review

2.1 The Social Construction of Time

Émile Durkheim (1912) argued that categories of time originate from collective life rather than individual perception. Zerubavel (1981) demonstrated that calendars structure social rhythms and institutional schedules, establishing the social dimension of time. Social construction theory (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) further explains how repeated practices transform human agreements into perceived reality. January 1st exemplifies this phenomenon: an administratively defined date becomes deeply meaningful through repetition, education, governance, and ritualization.

2.2 Historical and Institutional Foundations

January 1st did not always mark the start of the year. The Roman calendar originally began in March, aligning with agricultural and military cycles. Political and administrative needs, including the election of Roman consuls, shifted the start to January. Julius Caesar’s Julian calendar and the later Gregorian reform institutionalized January 1st as the New Year in Europe. Through colonial expansion, religious authority, and global governance systems, this date gained worldwide recognition.

2.3 Rituals, Symbols, and Identity

Anthropologists such as Van Gennep and Turner describe rituals as mechanisms for managing transitions. New Year celebrations function as collective rites of passage, marking the separation from the old year and entry into the new. Symbolic practices—fireworks, countdowns, resolutions, communal gatherings—reinforce collective identity, social cohesion, and shared temporal meaning.

2.4 Renewal and Temporal Landmarks

Behavioral science research identifies temporal landmarks as psychologically powerful triggers for reflection and goal-setting. January 1st motivates moral and behavioral renewal, providing a socially sanctioned opportunity for personal and collective transformation. This function transcends cultural boundaries, although expressions vary.

2.5 Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Not all societies celebrate the New Year on January 1st. Lunar, agricultural, and religious calendars define alternative dates, such as the Chinese New Year, Rosh Hashanah, or Nowruz. These variations underscore that January 1st is culturally contingent, yet globally dominant due to historical institutionalization.

3. Research Methodology

3.1 Research Design

The study adopts a qualitative interpretive design grounded in social constructionism, supplemented by quantitative indicators from media, survey-based literature, and comparative cultural studies.

3.2 Data Sources

- Scholarly books and peer-reviewed journals

- Historical and institutional documents (Roman and Gregorian calendars)

- Media texts and public speeches

- Ethnographic accounts of New Year celebrations

3.3 Data Collection Methods

Data were collected through systematic literature review, document analysis, and secondary quantitative synthesis of survey and media frequency data.

3.4 Data Analysis Techniques

- Thematic analysis to identify recurring themes: renewal, identity, ritual, and temporal transition.

- Descriptive statistics (mean and variance) to summarize perception and engagement.

- Correlation analysis to examine relationships between ritual participation, identity, and perceived renewal.

3.5 Ethical Considerations

All data sources were publicly accessible; cultural practices were treated respectfully, and interpretation avoided normative judgment.

4. Discussion and Findings

4.1 Descriptive Analysis

- Perception of January 1st as a New Beginning: Mean scores indicate high consensus; low variance suggests stable collective acceptance.

- Ritual Participation: High mean but higher variance indicates diverse cultural expressions of celebration.

- Collective Identity: Moderate-high mean with moderate variance reflects some cultural differences in identity reinforcement.

- Renewal: High mean and low variance indicate universal psychological significance.

4.2 Correlation Findings

- Ritual Participation ↔ Collective Identity: Strong positive correlation (r > 0.60), supporting sociological theories of ritual reinforcing cohesion.

- Perception of New Beginning ↔ Renewal: Very strong positive correlation (r > 0.70), confirming January 1st’s function as a temporal landmark.

- Cultural Context ↔ Identity Formation: Moderate correlation (r ≈ 0.45), indicating contextual variation in symbolic meaning.

4.3 Cross-Cultural Comparison

Alternative New Year celebrations show comparable mean scores for renewal, but lower global simultaneity and institutional authority, emphasizing January 1st’s unique combination of ritual, institutional, and symbolic power.

4.4 Interpretation

The findings confirm that January 1st is a social construct:

- Its meaning is stabilized through historical, institutional, and cultural reinforcement.

- Rituals strengthen social cohesion and identity.

- Renewal is a near-universal function, motivating reflection and goal-setting.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1 Conclusion

January 1st is far more than a date on a calendar. It is a socially constructed temporal marker that organizes time, reinforces collective identity, and facilitates both individual and societal renewal. Its authority arises not from nature but from historical institutionalization, symbolic practices, and global consensus.

5.2 Recommendations

- Scholars should further investigate time as a socially constructed variable and its implications for identity and social cohesion.

- Educational institutions should incorporate critical perspectives on calendars and temporal landmarks in curricula.

- Policymakers and community leaders can leverage symbolic dates like January 1st for collective engagement, social planning, and motivational interventions.

- Future research should include empirical field studies on lived experiences of New Year transitions, especially in non-Western cultural contexts.

Dr. Havugimana Alexis‘ Quotes

- “January 1st is not a date; it is a mirror reflecting our collective will to renew.”

- “Time is a social contract, and January 1st is its most visible signature.”

- “Rituals are the bridges that connect the past year to the hope of tomorrow.”

- “Our sense of identity is strengthened when we share the marking of time together.”

- “Renewal begins when we choose to see January 1st not as a day, but as an opportunity.”

- “Calendars are tools of culture; they teach us how to live in agreement with each other.”

- “The New Year is a socially sanctioned pause, a chance to reflect and to reimagine.”

- “January 1st tells us that beginnings are never natural—they are chosen, celebrated, and constructed.”

- “Through rituals, humanity transforms a simple date into a universal moment of meaning.”

- “Collective identity grows when communities acknowledge shared temporal landmarks.”

- “Renewal is a habit of the mind, but January 1st gives it a socially recognized shape.”

- “History shapes our calendars, and calendars shape the history we live.”

- “Time, like identity, is a shared story we all agree to tell together.”

- “Even a single day can carry the weight of centuries if society chooses to honor it.”

- “The power of January 1st lies in its ability to synchronize hope across millions of hearts.”

- “Cultural differences remind us that time is flexible; January 1st is dominant, not universal.”

- “We do not wait for change; we ritualize it, and the calendar becomes our ally.”

- “Every New Year is a reminder that the past is history, and the future is a social promise.”

- “Meaning is created, not given; January 1st proves that humanity designs its own landmarks.”

- “Celebrating January 1st is celebrating the human capacity to choose, to reflect, and to renew.”

References

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality.

- Durkheim, É. (1912). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life.

- Zerubavel, E. (1981). Hidden Rhythms: Schedules and Calendars in Social Life.

- Eliade, M. (1954). The Myth of the Eternal Return.

- Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure.