What do you know about Marburg Virus Disease?

By Dr.Alexis Havugimana

Marburg is a rare, severe, viral hemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola, which is spread by contact with blood or body fluids of a person infected with or who has died from the disease.

Marburg virus is the causative agent of Marburg virus disease (MVD), a disease with a case fatality ratio of up to 88%, but can be much lower with good patient care. Marburg virus disease was initially detected in 1967 after simultaneous outbreaks in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany; and in Belgrade, Serbia.

Marburg and Ebola viruses are both members of the Filoviridae family (filovirus). Though caused by different viruses, the two diseases are clinically similar. Both diseases are rare and have the capacity to cause outbreaks with high fatality rates.

Two large outbreaks that occurred simultaneously in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany, and in Belgrade, Serbia, in 1967, led to the initial recognition of the disease. The outbreak was associated with laboratory work using African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) imported from Uganda. Subsequently, outbreaks and sporadic cases have been reported in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Africa (in a person with recent travel history to Zimbabwe) and Uganda. In 2008, two independent cases were reported in travellers who had visited a cave inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies in Uganda.

Transmission

Initially, human MVD infection results from prolonged exposure to mines or caves inhabited by Rousettus bat colonies.

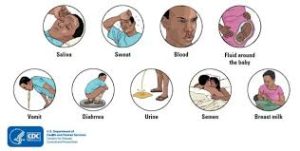

Marburg spreads through human-to-human transmission via direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and with surfaces and materials (e.g. bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids.

Health-care workers have frequently been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed MVD. This has occurred through close contact with patients when infection control precautions are not strictly practiced. Transmission via contaminated injection equipment or through needle-stick injuries is associated with more severe disease, rapid deterioration, and, possibly, a higher fatality rate.

Burial ceremonies that involve direct contact with the body of the deceased can also contribute in the transmission of Marburg.

People remain infectious as long as their blood contains the virus.

Symptoms of Marburg virus disease

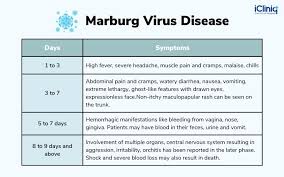

The incubation period (interval from infection to onset of symptoms) varies from 2 to 21 days.

Illness caused by Marburg virus begins abruptly, with high fever, severe headache and severe malaise. Muscle aches and pains are a common feature. Severe watery diarrhoea, abdominal pain and cramping, nausea and vomiting can begin on the third day. Diarrhoea can persist for a week. The appearance of patients at this phase has been described as showing “ghost-like” drawn features, deep-set eyes, expressionless faces, and extreme lethargy. In the 1967 European outbreak, non-itchy rash was a feature noted in most patients between 2 and 7 days after onset of symptoms.

Many patients develop severe haemorrhagic manifestations between 5 and 7 days, and fatal cases usually have some form of bleeding, often from multiple areas. Fresh blood in vomitus and faeces is often accompanied by bleeding from the nose, gums, and vagina. Spontaneous bleeding at venepuncture sites (where intravenous access is obtained to give fluids or obtain blood samples) can be particularly troublesome. During the severe phase of illness, patients have sustained high fevers. Involvement of the central nervous system can result in confusion, irritability, and aggression. Orchitis (inflammation of one or both testicles) has been reported occasionally in the late phase of disease (15 days).

In fatal cases, death occurs most often between 8 and 9 days after symptom onset, usually preceded by severe blood loss and shock.

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to clinically distinguish MVD from other infectious diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever, shigellosis, meningitis and other viral haemorrhagic fevers. Confirmation that symptoms are caused by Marburg virus infection are made using the following diagnostic methods:

- antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen-capture detection tests

- serum neutralization test

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- electron microscopy

- virus isolation by cell culture.

Samples collected from patients are an extreme biohazard risk; laboratory testing on non-inactivated samples should be conducted under maximum biological containment conditions. All biological specimens should be packaged using the triple packaging system when transported nationally and internationally.

Treatment and vaccines

Currently there are no vaccines or antiviral treatments approved for MVD. However, supportive care – rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids – and treatment of specific symptoms, improves survival.

There are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) under development and antivirals e.g. Remdesivir and Favipiravir that have been used in clinical studies for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) that could also be tested for MVD or used under compassionate use/expanded access.

In May 2020, the EMA granted a marketing authorisation to Zabdeno (Ad26.ZEBOV) and Mvabea (MVA-BN-Filo). against EVD . The Mvabea contains a virus known as Vaccinia Ankara Bavarian Nordic (MVA) which has been modified to produce 4 proteins from Zaire ebolavirus and three other viruses of the same group (filoviridae). The vaccine could potentially protect against MVD, but its efficacy has not been proven in clinical trials.

Marburg virus in animals

Rousettus aegyptiacus bats are considered natural hosts for Marburg virus. There is no apparent disease in the fruit bats. As a result, the geographic distribution of Marburg virus may overlap with the range of Rousettus bats.

African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) imported from Uganda were the source of infection for humans during the first Marburg outbreak.

Experimental inoculations in pigs with different Ebola viruses have been reported and show that pigs are susceptible to filovirus infection and shed the virus. Therefore, pigs should be considered as a potential amplifier host during MVD outbreaks. Although no other domestic animals have yet been confirmed as having an association with filovirus outbreaks, as a precautionary measure they should be considered as potential amplifier hosts until proven otherwise.

Precautionary measures are needed in pig farms in Africa to avoid pigs becoming infected through contact with fruit bats. Such infection could potentially amplify the virus and cause or contribute to MVD outbreaks.

Prevention and control

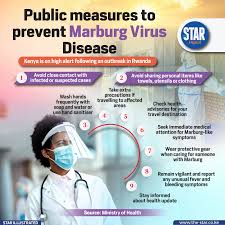

Good outbreak control relies on using a range of interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing, a good laboratory service, safe and dignified burials, and social mobilization. Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks. Raising awareness of risk factors for Marburg infection and protective measures that individuals can take is an effective way to reduce human transmission.

Risk reduction messaging should focus on several factors:

- Reducing the risk of bat-to-human transmissionarising from prolonged exposure to mines or caves inhabited by fruit bat colonies. During work or research activities or tourist visits in mines or caves inhabited by fruit bat colonies, people should wear gloves and other appropriate protective clothing (including masks). During outbreaks all animal products (blood and meat) should be thoroughly cooked before consumption.

- Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission in the communityarising from direct or close contact with infected patients, particularly with their body fluids. Close physical contact with Marburg patients should be avoided. Gloves and appropriate personal protective equipment should be worn when taking care of ill patients at home. Regular hand washing should be performed after visiting sick relatives in hospital, as well as after taking care of ill patients at home.

- Communities affected by Marburgshould make efforts to ensure that the population is well informed, both about the nature of the disease itself and about necessary outbreak containment measures.

- Outbreak containment measuresinclude prompt, safe and dignified burial of the deceased, identifying people who may have been in contact with someone infected with Marburg and monitoring their health for 21 days, separating the healthy from the sick to prevent further spread and providing care to confirmed patient and maintaining good hygiene and a clean environment need to be observed.

- Reducing the risk of possible sexual transmission.Based on further analysis of ongoing research, WHO recommends that male survivors of Marburg virus disease practice safer sex and hygiene for 12 months from onset of symptoms or until their semen twice tests negative for Marburg virus. Contact with body fluids should be avoided and washing with soap and water is recommended. WHO does not recommend isolation of male or female convalescent patients whose blood has been tested negative for Marburg virus.

Controlling infection in healthcare settings

Healthcare workers should always take standard precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe and dignified burial practices.

Healthcare workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Marburg virus should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with MVD, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Marburg infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories.

Marburg viral persistence in in people recovering from Marburg virus disease

Marburg virus is known to persist in immune-privileged sites in some people who have recovered from Marburg virus disease. These sites include the testicles and the inside of the eye.

- In women who have been infected while pregnant, the virus persists in the placenta, amniotic fluid and foetus.

- In women who have been infected while breastfeeding, the virus may persist in breast milk.

Relapse-symptomatic illness in the absence of re-infection in someone who has recovered from MVD is a rare event, but has been documented. Reasons for this phenomenon are not yet fully understood.

Marburg virus transmission via infected semen has been documented up to seven weeks after clinical recovery. More surveillance data and research are needed on the risks of sexual transmission, and particularly on the prevalence of viable and transmissible virus in semen over time. In the interim, and based on present evidence, WHO recommends that:

- Male Marburg survivors should be enrolled in semen testing programmes when discharged (starting with counselling) and offered semen testing when mentally and physically ready, within three months of disease onset. Semen testing should be offered upon obtention of two consecutive negative test results.

All Marburg survivors and their sexual partners should receive counselling to ensure safer sexual practices until their semen has twice tested negative for Marburg virus.

Survivors should be provided with condoms.

Marburg survivors and their sexual partners should either:

abstain from all sexual practices, or

observe safer sexual practices through correct and consistent condom use until their semen has twice tested undetected (negative) for Marburg virus.

Having tested undetected (negative), survivors can safely resume normal sexual practices with minimized risk of Marburg virus transmission.

Male survivors of Marburg virus disease should practice safer sexual practices and hygiene for 12 months from onset of symptoms or until their semen twice tests undetected (negative) for Marburg virus.

Until such time as their semen has twice tested undetected (negative) for Marburg, survivors should practice good hand and personal hygiene by immediately and thoroughly washing with soap and water after any physical contact with semen, including after masturbation. During this period used condoms should be handled safely, and safely disposed of, so as to prevent contact with seminal fluids.

All survivors, their partners and families should be shown respect, dignity and compassion.

WHO response

WHO aims to prevent Marburg outbreaks by maintaining surveillance for Marburg virus disease and supporting at-risk countries to develop preparedness plans. The following document provides overall guidance for control of Ebola and Marburg virus outbreaks:

- Ebola and Marburg virus disease epidemics: preparedness, alert, control, and evaluation

When an outbreak is detected WHO responds by supporting surveillance, community engagement, case management, laboratory services, contact tracing, infection control, logistical support and training and assistance with safe burial practices.

WHO has developed detailed advice on Marburg infection prevention and control:

- Infection prevention and control guidance for care of patients with suspected or confirmed Filovirus haemorrhagic fever in health-care settings, with focus on Ebola

What is the situation in Rwanda?

There are currently 36 confirmed cases of Marburg in Rwanda, with 25 people being cared for in isolation, according to the government’s latest update.

According to the WHO, on September 30 when there were 26 confirmed cases, 70 percent of the cases were in healthcare workers in two of the country’s healthcare facilities, which were not named.

It’s not uncommon to see outbreaks in healthcare facilities, especially in low-resourced healthcare facilities that may not have sufficient infection control,” Roess said.

Additionally, Rwanda is monitoring 300 people who have come into contact with known cases.

A fruit bat hangs upside-down in its cage, on July 29, 2023 when the World Health Organization said Equatorial Guinea had confirmed its first outbreak of Marburg disease [Bob Child/AP]

Where has the Marburg virus spread?

On September 27, Rwanda’s Ministry of Health confirmed the latest outbreak of the Marburg virus.

The current outbreak has only been reported in Rwanda so far.

There were fears that the virus had reached Germany when two passengers on a train from Frankfurt to Hamburg contacted doctors, fearing they had the virus.

However, local authorities announced on Thursday that both had tested negative in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, where a sample from the inner cheek, called a buccal swab, or blood is tested. It tests genetic material from a specific organism, which in this case is the virus.

Small outbreaks of the virus have occurred in recent years including West Africa’s first outbreak in Guinea in 2021, Ghana’s first outbreak in 2022 and the first outbreaks in Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea in 2023.

These were quickly contained. In Equatorial Guinea, 17 confirmed and 23 probable cases were reported. “12 of the 17 confirmed cases died and all of the probable cases were reported deaths,” according to WHO. In Tanzania, there were one probable and eight confirmed cases, of which five resulted in death.

According to the CDC, in Guinea, only one case was diagnosed after the death of the patient; in Ghana, three cases emerged leading to two deaths.

“We know that an infectious disease that emerges in one area has the potential to become a problem across the globe,” Roess said.

How dangerous is the latest Marburg outbreak?

WHO has assessed the risk of this outbreak to be “very high at the national level, high at the regional level, and low at the global level”.

Is there a vaccine or treatment?

There are no approved vaccines or treatments for the virus

What is the situation for marburg virus in The East African Community (EAC) ?

The East African Community (EAC) is a regional intergovernmental organisation of eight (8) Partner States, comprising the Republic of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Kenya, the Republic of Rwanda, the Federal Republic of Somalia, the Republic of South Sudan, the Republic of Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania, with its headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania. The Federal Republic of Somalia was admitted into the EAC bloc by the Summit of EAC Heads of State on 24th November, 2023 and became a full member on 4th March, 2024

The East African Community (EAC) Secretariat has called for a swift and coordinated regional response to contain the ongoing Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) outbreak declared in Rwanda. The outbreak poses a serious threat to regional health security and requires urgent action from all EAC Partner States to prevent its spread across borders.

On the 27th September 2024 Rwanda’s Ministry of Health declared the Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) outbreak and as of 30th September, 2024 there were 29 confirmed cases and 10 deaths with more than 297 contacts under close monitoring and healthcare workers have been disproportionately affected. The World Health Organization (WHO) has raised concerns about the potential regional spread of the disease due to confirmed cases in districts near the borders of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda, and Tanzania.

Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA, 1 October 2024 – The Ministry of Health of the Republic of Rwanda declared a Marburg virus disease (MVD) outbreak on 27 September 2024. As of 30 September, 27 confirmed cases and 9 deaths have been reported; most of the cases are health care workers. Over 297 contacts have been registered and are under follow-up.

The Ministry of Health is working tirelessly in collaboration with relevant partners to contain the deadly virus through enhanced preventive measures in all health facilities. Contact tracing is underway, and cases have been isolated for treatment. The Ministry of Health further urged Rwandans to remain vigilant and strengthen preventive measures by ensuring hygiene, washing hands with soap, sanitizing hands, and taking necessary precautionary measures when in contact with other individuals.

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is a severe and often fatal zoonotic haemorrhagic illness caused by the Marburg virus. The virus is usually transmitted to humans from fruit bats. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with an infected person’s body fluids, or with equipment and materials contaminated with infectious blood or tissues. There is currently no vaccine or specific treatment for MVD, so supportive therapy should be initiated immediately for any individuals presenting with the disease. The same infection prevention and control protocols used for other viral haemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola, should be followed to prevent transmission.

On September 29th, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) dispatched a team of experts to aid in response efforts in Rwanda. Africa CDC is also collaborating with the Ministry of Health and neighbouring countries of Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania, and DR Congo to assist in addressing the cross-border aspects of the outbreak and to provide guidance on regional surveillance strategies to contain the outbreak.

The Minister of Health of Rwanda, H.E. Sabin Nsanzimana, will join the Africa CDC Press Briefing on Thursday, October 3, alongside the Director General of Africa CDC, Dr. Jean Kaseya, to discuss Rwanda’s efforts in curbing the Marburg virus.

About Africa CDC

The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) is a continental autonomous public health agency of the African Union that supports member states in efforts to strengthen health systems and improve surveillance, emergency response, and prevention and control of diseases.

“There is an urgent need for a coordinated regional response to contain the spread of this highly infectious virus through swift identification, isolation, and treatment of cases and enhanced screening at borders and health facilities,” said Hon. Andrea Aguer Ariik Malueth, EAC Deputy Secretary General, in charge of Infrastructure, Productive, Social & Political sectors

He called for Partner States to strengthen their public awareness and infection control protocols including handwashing, avoiding physical contact with symptomatic individuals and surveillance at borders and health facilities.

Marburg virus is a severe zoonotic disease, similar to Ebola, and is associated with a high fatality rate varied from 24% to 88% depending on virus strain and case management. Transmission occurs through direct contact with bodily fluids of infected individuals or contaminated surfaces. As there is no specific vaccine or treatment, supportive care remains the main form of medical intervention.

Tanzania’s previous experience with a Marburg outbreak in the Kagera region in 2023, highlighted the importance of rapid contact tracing and community engagement. The EAC is urging Partner States to share lessons learnt and technical expertise to inform the ongoing response efforts. Meanwhile, Rwanda, recognized for its robust healthcare infrastructure, is currently managing the outbreak with international support, but the scale of the challenge underscores the need for regional collaboration.

Symptoms of Marburg Virus Disease typically include fever (often high), severe headache, muscle aches and pains, fatigue and weakness. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as severe diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and bleeding from various parts of the body (in later stages of the disease). To Reduce the risk of contracting Marburg, the public is advised to:

- Practice proper hand hygiene using soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizers.

- Avoid contact with fruit bats and their excretions, as these are considered the natural hosts of the virus.

- Practice safe burial practices to minimize exposure to bodily fluids of individuals who have died from MVD.

- Wear personal protective equipment (PPE) when caring for infected individuals or handling animals that may be reservoirs of the virus.

- Avoid contact with nonhuman primates in endemic areas, as these can also transmit the virus.

Individuals suspecting that they may have contracted Marburg should:

- Seek medical care immediately as early supportive treatment is crucial to improve survival chances.

- Isolate themselves to prevent spreading the virus to others.

- Notify local health authorities or go to the nearest healthcare facility for assessment.

- Avoid contact with others, particularly through bodily fluids, until the suspicion of Marburg infection is ruled out.

The East African Community Secretariat in collaboration with partners including the German Government through GIZ and KfW is supporting the Partner States response and preparedness efforts to the ongoing MVD and Mpox outbreaks and further enhance pandemic preparedness efforts with a focus on enhancing regional resilience to health emergencies. The major interventions areas include the development of a pool of the Rapidly Deployable Experts (RDE) to ensure quick deployment of experts in outbreak areas; strengthening Risk and Crisis Communication, established 43 Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) facilities in border areas and prioritized the training of border staff and health workers.

Furthermore, the EAC Secretariat is supporting the Partner States laboratory testing capacities through supply of diagnostic PCR kits for Marburg virus (filo viruses) and Monkeypox virus, facilitating field deployment of the existing Mobile laboratories at strategic locations and the donation of additional laboratory equipment such as sequencers.

All these efforts have now positioned the EAC Secretariat as a key player in the preparedness and response to the current and future health threats, highlighting the region’s proactive approach to safeguarding public health.

Dr. Alexis Havugimana

References

- WHO press release on announcement by Rwanda, 28 September 2024. Available at: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/rwanda/news/rwanda-reports-first-ever-marburg-virus-disease-outbreak-26-cases-confirmed

- WHO factsheet – Marburg virus disease. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/marburg-virus-disease

- World Health Organization (March 2009). Hand hygiene technical reference manual: to be used by health-care workers, trainers and observers of hand hygiene practices. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241598606

- Ebola and Marburg diseases screening and treatment center design training. Available at: https://openwho.org/courses/ebola-marburg-screen-treat-facilities

- World Health Organization (2 June 2023). Disease Outbreak News; Marburg virus disease in the United Republic of Tanzania. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON471

- Building research readiness for a future filovirus outbreak, Workshop February 20 – 22, 2024, Uganda. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2024/02/20/default-calendar/building-research-readiness-for-a-future-filovirus-outbreak-workshop-february-20-22-2024-uganda

- WHO Technical Advisory Group – candidate vaccine prioritization. Summary of the evaluations and recommendations on the four Marburg vaccines. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-technical-advisory-group—candidate-vaccine-prioritization.–summary-of-the-evaluations-and-recommendations-on-the-four-marburg-vaccines

- Marburg virus vaccine landscape. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/marburg-virus-vaccine-landscape